The institution of the Presidency

The president of the State of Israel is the head of state, according to the law. The influence of the institution of the Presidency has traditionally been based, to a great extent, on its dignified national character and ability to serve as a symbol of national unity, representing the core values of the state. Its activities are therefore geared toward strengthening partnerships among Israeli citizens and bringing them together; deepening their identification with their state and its national symbols; fostering social cohesion, national pride, and the connection between Israel and Diaspora Jewry; and nurturing the values of morality, equality, and peace in Israel.

The origins of the institution of the Israeli President

When the State of Israel was founded, the Provisional State Council (the elected authority that preceded the Knesset) decided, on May 16, 1948, to elect Dr. Chaim Weizmann, the longstanding president of the World Zionist Organization, to the role of president of the Provisional State Council. Toward the end of the War of Independence, after the elections for the Constituent Assembly (effectively the First Knesset), the Knesset elected Weizmann, on February 17, 1949, as the first president of the State of Israel. The Israeli leadership’s conception of the Presidency, as reflected in the deliberations of the Provisional State Council’s Constitution Committee, was, on the whole, similar to Herzl’s original vision: “The role of the President will be that of a non-partisan head of state, representing the land and the nation in their entirety, domestically and externally” (from the discussion agenda for the Provisional State Council’s Constitution Committee, which was part of the proposed constitution drafted by Dr. Leo Kohn).

In 1951, the Knesset passed the State President (Tenure) Law 5711-1951, which as its name hints, was not about the powers of the President, but only the length of his tenure and the mechanism for his election.

On June 16, 1964, the Knesset passed Basic Law: The President of the State.

Swearing in of Israel’s first president, Chaim Weizmann

Credit: David Eldan, GPO

The Functions of the Presidency

Dr. Chaim Weizmann’s election as the First President of the State of Israel was overclouded by significant ambiguity about the powers and influence of the President. The following words, written by President Weizmann, attest to his feelings at the time: “It is not that I do not value the great honor that this position confers upon its holder, but the President’s duties and responsibilities have not been made clear to me.… For example, I was told that the President is a symbol. To date, I have been unable to understand this vague statement, as well as who determines the symbolic importance of the President of the State.”

President Isaac Herzog being sworn in

Credit: Haim Zach, GPO

The First Zionist Congress awarded the title nasi to Theodor Herzl, the founder of the World Zionist Organization. In his novel Altneuland, Herzl articulated his vision for a Jewish state, in which the Zionist Congress would elect a nasi, a president, every seven years. The nasi, in Herzl’s vision, was mainly a figurehead, standing above the political fray and symbolizing national unity.

In time, the official functions of the president were anchored in a Basic Law and other legislation, and much of the original vagueness was eliminated. Nevertheless, successive Israeli Presidents would wield immense influence over the State of Israel and Israeli society, because they operate in areas beyond the contours of the role delineated by the legislator, in accordance with each president’s personality, worldview, background before entering office, and esteem and trust from the public.

The nature and extent of the president’s influence has been defined as “soft power.”

As the State of Israel approaches its eightieth year of independence, the functions of the Presidency are being shaped in the spirit of President Isaac Herzog’s vision for Israel to reach this milestone more cohesive and less divided, bravely and fearlessly working through the conflicts within its society, in a manner that will allow it to flourish and grow stronger.

The best path to achieving these objectives, President Herzog believes, runs through listening, respect, dialogue, deep mutual acquaintance, and the construction of domestic, national, regional, and international bridges.

Basic Law: The President of the State

Israeli law states that the president is the head of state. The president is elected by the Knesset for a single seven-year term, in a secret ballot conducted during a special sitting of the Knesset.

Basic Law: The President of the State stipulates the powers entrusted to the president and his other roles, including:

- Signing laws after they are passed by the Knesset;

- Fulfilling the roles assigned to the president in Basic Law: The Government, chiefly assigning the task of forming a government after consultations with representatives of the elected parliamentary groups;

- Accrediting the State of Israel’s diplomatic representatives and receiving the credentials of diplomatic representatives sent to Israel by foreign states;

- Signing treaties with foreign states approved by the Knesset;

- Carrying out all other responsibilities assigned to him by law in connection with the appointment and removal from office of judges and other office-holders.

In addition, the law gives the president the power to pardon criminals and commute their sentences. It also states that the President “shall carry out any other responsibility, and hold every other power assigned to him by law.”

The powers of the Presidency

The two most familiar and significant formal presidential authorities, anchored, of course, in Israel’s Basic Laws, are the power to assign the task of forming a government and the power to grant pardons. In addition to these, the President retains other powers, as detailed below.

Assigning the task of forming a government

Basic Law: The Government defines in detail the formal process whereby the president assigns the task of forming a government to a member of Knesset after elections or following the resignation of a prime minister. There are two main reasons for the president’s involvement in this issue: first, the stability of the office of the president, whose tenure spans governments’ terms in office and Knesset sessions and provides another, broader, different perspective to the whole process. The second reason is the president’s ability, as the head of state, to work to mediate between partisan agendas and camps, specifically at the most polarized and divisive times in national life—elections to the Knesset.

According to the law, the president consults representatives of the parliamentary groups in the Knesset and assigns the task of forming a government to a member of the Knesset, who has agreed to do so. As a rule, successive presidents have tended to assign the task of forming a government to the person who seems to have the best prospect of doing so. It is worth noting that traditionally, presidents have worked to broaden the parameters of coalitions to include as broad a spectrum as possible of groups and voices in Israeli society, to influence the shape of public policy. The consultation process includes discussions between the president and representatives of the parliamentary groups about timely issues and of course the question of the formation of a government.

Granting pardons

The president possesses the legal authority to pardon offenders and modify their sentences by reducing or commuting them.

Anyone may write to the president to request a pardon, either personally, through someone authorized to speak on their behalf, or through a first-degree relative. Individuals may ask the president to modify any sentence imposed by a court, including the following sentences: imprisonment; community service; driving disqualifications; fines, including traffic fines and administrative fines; and life imprisonment, which may be commuted, and requests may also be submitted for the further commutation of already-commuted life sentences. Individuals may also request reductions to xxx; the erasure of records of traffic violations; and modifications to disciplinary action taken against licensed traders (suspension or cancellation of a license).

According to established policy, the President considers a request for a pardon only after the end of all judicial proceedings in the case.

Requests for pardons are addressed to the president and are conveyed to the Pardons Department in the Ministry of Justice or Ministry of Defense, depending on the context. Requests for pardons are examined after receiving the information and opinions necessary for a decision to be made, including facts and opinions from relevant authorities. At the end of this process, the opinions are presented to the minister of justice or minister of defense before a recommendation is made to the president.

In all the years of the existence of the institution of pardons, the act of granting a pardon has also been an expression of each president’s vision, worldview, and values system, which play a significant and deliberate role in his decision regarding whether or not to grant a pardon.

The president’s signature on each pardon requires the countersignature of the relevant minister.

Israeli society

One of the informal but significant functions of the Presidency throughout the ages has been to give a voice to the diversity of Israeli society, shining a spotlight on different groups and issues—each president in accordance with his own vision.

Israeli presidents place at the core of their time in office the fostering of mutual responsibility in Israeli society and the importance of giving consideration to every citizen and community. The advancement of Israel’s national resilience and social cohesion, acknowledging the full diversity and complexity of the Israeli mosaic, and the enhancement of dignified conduct, solidarity, and a sense of belonging are among the most important of the president’s informal roles. Consequently, President Isaac Herzog is extensively involved in connecting people, building bridges, and establishing a respectful and dignified safe space for arguments and discussions on sensitive matters.

Similarly, President Herzog has been working to build a powerful engine for cultivating the future leadership of Israel and the Jewish world.

Israeli presidents’ concern for the various groups in Israeli society has often been reflected in efforts to lay solid foundations for social solidarity, striving to shrink the existing rifts within society.

Additionally, successive presidents have also dealt with issues related to the Jewishness of the State of Israel—historically, religiously, and culturally.

Signing legislation

The president’s signature is required to give official effect to laws; this is true of all laws, other than laws relating to his powers. His signature appears alongside the countersignature of the prime minister or a minister.

The president’s signature on a law is required but nevertheless does not delay a law’s entry into force.

Accreditation of diplomats and appointment of judges

As the head of state, the president receives the credentials of diplomatic representatives in Israel and confirms the accreditation of Israel’s representatives abroad. Additionally, the president makes appointments to all judicial instances in Israel and signs the writs of appointment of judges, dayanim (judges in Jewish religious courts), and qadis (judges in Muslim religious courts). Similarly, the president appoints various office-holders as defined by law, including the president of the Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, the chairman of the Prisoner Rehabilitation Authority, the president of Magen David Adom, members of the Council for Higher Education, members of the National Council for Civilian Research and Development, and more.

Additional roles

Besides the presidential powers defined by law, many see the institution of the Presidency, which may be called the “fourth branch of government,” as a necessary and welcome element of the Israeli system of government, precisely because its activities and influence lie beyond the remit of the powers granted to this institution in law.

In virtue of his position above politics, the president provides support to citizens from all walks of Israeli society, a bridge-building figure working out of a residence that is also the People’s House.

The president also works to establish and lead groundbreaking domestic and international partnerships on issues related to his core activities, such as the fight against the climate crisis, which threatens humanity’s future.

The mere existence of a unifying personal figure as the head of state, it is widely accepted, contributes to the public’s ability to conceptualize and identify with the national framework of their state. The Presidency thus contributes to a sense of stability, which is also inherent in the separate timetable for elections to the Presidency and elections to the Knesset.

Foreign relations

Although Basic Law: The President of the State does not say so explicitly, one of the president’s best-known and important functions is to represent the State of Israel before the international community and Diaspora Jewry.

The president’s departure from the country is brought the attention of relevant government officials, in virtue of the fact that notwithstanding the Presidency’s independence, there is great value to cooperation and synergy between the various institutions of government.

Presidential visits to foreign states are often historic and lay the foundations for deeper relations with world leaders and their nations.

The connection with Diaspora Jewry, led by the President, has always contributed a great deal to the building of meaningful and influential bridges between Diaspora Jewry and the State of Israel, impacting what happens in the Jewish world.

The president as a representative figure

The president’s image over the years as one who can bridge differences and stand above political disputes strengthens the public’s confidence in him. The president, therefore, retains great importance as the figure who represents the state and enables its citizens to identify with it, both during crises and challenging moments and in times of pride and hope.

The first lady of the State of Israel

The roles and activities of the first lady are not formally defined by law or custom. Over the years, each first lady has filled the position with content as she saw fit and has worked to advance significant social and communal issues that were close to her heart.

For more information on the vision and work of First Lady Michal Herzog, see the dedicated page on the Office of the President’s website.

The figure of the President

The president is elected by the Knesset, and so his election would seem to be political. Nevertheless, the representative and symbolic nature of the Presidency and the fact that the president is elected in a secret ballot mean that the Knesset usually elects individuals of stature and vision, who have made contributions to the Zionist enterprise and the State of Israel and have earned great admiration from all parts of Israeli society.

Many Jews around the world see the president as not only the president of the State of Israel, but also as the president of the Jewish People. Much like the nasi of the Sanhedrin in the Mishnaic and Talmudic periods, the president of the State of Israel acts in virtue of his personality and status to represent and speak for Israel before heads of state, senior figures, and important institutions around the world.

The Israeli Supreme Court has opined on the figure of the president and the institution of the Presidency: “The President symbolizes the state and its moral and democratic values… With his status, he represents the value of the state and the lines that unite and connect the different parts of Israeli society. Through his character, he is expected to reflect the goodness, the beauty, the morality, and the distinctiveness of the Israeli population. He is expected to serve as an example and a role model in his performance of his position and conduct of his private life alike” (HCJ 5699/07 Anon. (A.) v. Attorney General).

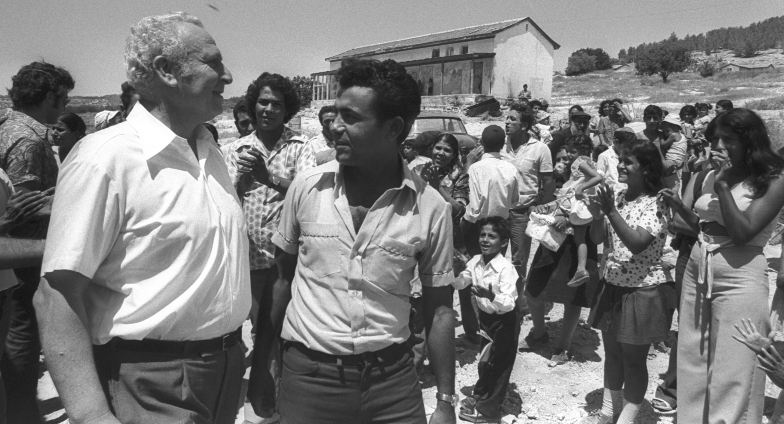

Israel’s fourth president, Ephraim Katzir, in Eshtaol

Credit: Mosheh Milner, GPO

The roots of the title nasi (“president”)

The title nasi, the modern Hebrew word for “president,” originates in the Hebrew Bible. The Hittites of Hebron addressed Abraham using the honorific “nasi of God among us” (Genesis 23:6), and the heads of the Israelite tribes in the wilderness also bore the title nasi. During the Second Temple period and the Mishnaic and Talmudic eras, nasi was the title of the head of the Sanhedrin, who presided over the supreme religious and judicial institution of the Jews of the Land of Israel and represented the people before the Roman authorities.

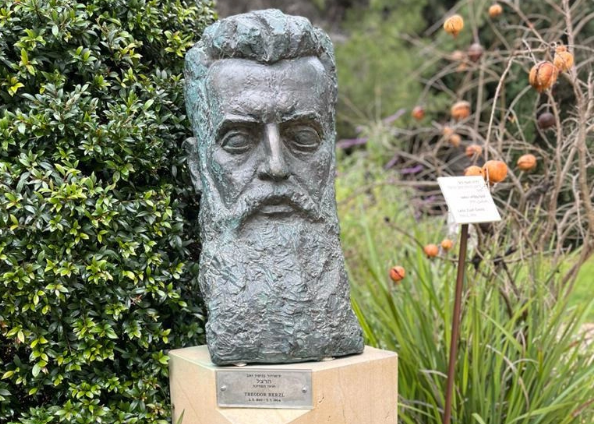

Statue of Theodore Herzl in the presidential gardens

Credit: The President’s Spokesperson’s Office

Basic Law: The President of the State

In 1964, the Knesset passed Basic Law: The President of the State.

Its main points are:

- The President is the head of state.

- The President’s place of residence is Jerusalem.

- Every Israeli citizen, who is a resident of Israel, is eligible to be a candidate for the office of President of the State;

- A candidate for the role of President must be nominated by at least ten Members of the Knesset;

- The president is elected by the Knesset in a secret ballot, and after his election, he must make a declaration of allegiance before the Knesset;

- The president’s term of office lasts seven years. In the past, before the law was amended in 1998, the length of a presidential term was five years, and it was possible to be elected to the office more than once.

- The law grants the president substantive immunity in connection with his functions and powers. This immunity means that the President is not accountable to any court of law for anything connected with his functions or powers. The purpose of this substantive immunity is to protect the status of the president as the head of state, above the other branches of government.

- In addition to his substantive immunity, the president is also granted procedural immunity, and he cannot face criminal charges (nevertheless, the president may be investigated and required to give testimony).

- The president’s procedural immunity expires at the end of his term in office.

- The president may temporarily cease to perform his duties (with the consent of the Knesset) in three cases: leaving the borders of the state; a request from the president to the Knesset House Committee for a leave of absence (for any reason); a decision by the House Committee, by a majority of two-thirds of its members, to require the President to take a leave of absence for medical reasons.

- If the president is absent for any of the above reasons, or if the president passes away and his successor has not yet been elected, he is substituted by the speaker of the Knesset.

- The law allows for the president to be removed from office following a hearing before the House Committee, and only with the consent of at least 90 members of the Knesset.

The Presidential Standard

The Presidential Standard is the symbol that represents the President of Israel. It is a blue square with silver margins, olive branches, the Menorah, and the word “Israel” in the middle. It was designed by brothers Gabriel and Maxim Shamir.

Despite the great resemblance with the official Emblem of Israel, there are several differences between the Presidential Standard and the national symbol. The Presidential Standard, for example, is a square, whereas the Emblem of Israel is in the shape of a shield; moreover, the Menorah, olive branches, and the word “Israel” on the Presidential Standard are white or silvery-grey, whereas the same symbols appear in gold on the emblem of the state.

The Presidential Standard is used to symbolize the President’s presence, mostly at official ceremonies and events. Consequently, for example, it is customary for the Presidential Standard to be flown at the Knesset building and in its plenum during ceremonies attended by the President. The raising of the Presidential Standard is part of the reception ceremony that the Knesset hosts for the President, and it is taken down when the President leaves the building. The Presidential Standard is permanently displayed in the President’s Bureau, the Jerusalem Room (the Audience Room), and the Great Hall of the President’s Residence. It also flies at the top of a flagpole, alongside the flag of the State of Israel, in the President’s Residence Gardens.

Transfer of presidential standard from outgoing president, Reuven (Rubi) Rivlin to incoming president, Isaac Herzog

Credit: Haim Zach, GPO

Traditional government portrait against backdrop of presidential standard

Credit: Avi Ohayon, GPO

The Fourth Branch of Government: On the Institution of the Presidency (by Yinon Guttel-Klein)

Israeli public discourse has been accustomed to doubting the importance of the institution of the Presidency, seeing it as an empty symbol and ignoring its tremendous influence on the country over the years. A look at the past reveals a different picture—with implications for the future.

“I am familiar with the institution of the Presidency,” President Yitzhak Navon told Labor Party colleagues. “I knew what I was getting myself into. It is absolutely clear to me what I will do as President. For this, I need no addition to my powers.” “This isn’t a government resolution,” President Yitzhak Ben-Zvi told an aide. “Here, I have something to say.”

Despite the parallels between the two Jerusalemite presidents, Ben-Zvi and Navon, it is especially surprising to find similar remarks from them about the contours of the powers of Israel’s head of state. It is surprising because their respective presidencies evolved in completely different political contexts: President Ben-Zvi was in office at a time when the executive branch was headed by his close friend Ben-Gurion, and their paths had been intertwined since their adolescent years. There were certainly disagreements and disappointments between the two men, but there is no doubt that the discourse between the Presidency and the Government (and its leader at the time) was cordial, collegial, and based on similar values and a shared past. In contrast, President Navon served in tandem with Prime Minister Menachem Begin, who had not only grown up in a completely different and practically opposite world, but was also the greatest rival of Navon’s party patron. Nevertheless, it was clear to both Ben-Zvi and Navon what the powers of the President were—and how much influence he exercised beyond those powers.

Timetable: Knesset Elections and Government Formation

- Elections to the Knesset

- Final date for the official publication of the election results: within 8 days of the elections, the official results are published in the Official Gazette (§11 of Basic Law: The Knesset)

- According to convention, the results are presented to the President by the chairman of the Central Elections committee on the day of the official publication of the results

- Consultations with Knesset parliamentary groups

- Final date to assign the task of forming a government: the President assigns the task of forming a government to a member of the Knesset after consultations with the parliamentary groups within 7 days of the publication of the official results (art. 7(a) of Basic Law: The Government)

- After the President assigns the task of forming a government, he must inform the speaker of the Knesset, who must inform the Knesset (art. 13(a) of Basic Law: The Government).

Continuation of the process according to Basic Law: The Government (henceforth: “the law”)

The precise dates depend on the date of the President’s decision to assign the task of forming a government.

1. According to art. 8 of the law, the member of the Knesset to whom the President has assigned the task of forming a government has 28 days to perform his task. The President is entitled to prolong this period by additional periods of no more than 14 days in total (altogether, no more than 42 days).

2. Should the timeframe given to the member of the Knesset have elapsed and he has not been able to form a government, or has informed the President that he is unable to form a government or has presented a government and the Knesset has rejected the request to express confidence in it, the President has two options and must exercise one of them within three days (art. 9(a) of the law):

- a. The President may assign the task of forming a government to another member of the Knesset, who has informed the president that he is willing to assume the task. The member of the Knesset to whom the President assigns the task of forming a government (in the second round) will have a period of 28 days to form a government, which cannot be extended (art. 9(c) of the law);

- b. The President may inform the speaker of the Knesset that he sees no possibility of arriving at the formation of a government.

3. The President is entitled to consult the representatives of the Knesset parliamentary groups again before selecting one of the above options (art. 9(b) of the law).

4. Should the President inform the speaker of the Knesset that he sees no possibility of arriving at the formation of a government or that he has assigned the task of forming a government to a member of the Knesset (in the second round) and that member of the Knesset has not been able to form a government, or has informed the President that he is unable to form a government or has presented a government and the Knesset has rejected the request to express confidence in it, a majority of Knesset members are entitled to ask the president, in writing, to assign the task of forming a government to a certain member of the Knesset, who has agreed to it in writing, within 21 days (art. 10(a) of the law).

5. If such a request is submitted, the President must assign the task to the member of the Knesset mentioned in the request within 2 days (art. 10(b) of the law), and the member of the Knesset who has been assigned the task has 14 days to form a government (art. 10(c) of the law).

6. If such a request is not submitted, or if the member of the Knesset has not formed a government (in the third round) or has informed the President that he is unable to form a government or that a government has been presented and the Knesset has not expressed confidence in it, the Knesset shall be deemed to have decided to dissolve itself before the end of its term, and elections will take place within 90 days (art. 11 of the law).

7. Should a member of the Knesset be able (in any of the rounds) to form a government, he shall inform the president and the speaker of the Knesset, and a session for the purpose of forming a government shall be set within 7 days (art. 13(b) of the law).